The Proposal Stasis

Last time we ended by covering the evaluation stasis. We’ll continue using the evaluation stasis today as we move to the proposal stasis. This is because proposals always imply some degree of evaluation. That is, in order to propose a solution to some problem, you have to begin by evaluating the current state of things to show that they’re bad in some important way and in need of fixing–only then does it make sense or feel exigent to propose a solution and fix what needs fixing.

But! The amount of evaluating you do versus the amount of proposing you do depends on the particulars of your topic and, as we shall see later today, on your target audience.

For example: most people in Michigan already agree that our roads are in horrible shape and in need of fixing. What people disagree about is the solution: what the best way to fix the roads is. Indeed, back in November of 2015, a roads funding bill narrowly made it through the Michigan House and Senate, and before Gov. Snyder went on to sign it, it faced a barrage of controversy:

If you wrote a paper making an argument about this issue, the exigence (the thing that would be provoking you to write) would probably not be that people don’t get how bad Michigan’s roads are–they certainly do. Rather, the problem (the nature of the disagreement) is that people can’t agree on how to fix them.

Literally what this means for our hypothetical paper is that you wouldn’t need to spend many paragraphs persuading your reader that Michigan’s roads are in bad shape. If your audience is the average Michigander, the odds are that they’d already agree with you. So instead, you would want to prioritize the solution to the problem. The goal in this case is to convince your reader that your solution–the one you’re proposing–is the right solution, the better solution. Put otherwise, you would want to emphasize the “proposal” over the “evaluation” (although part of making this work is also, of course, evaluating other people’s proposals to show that yours is the better one–a kind of extra set of evaluations that comes after you begin to make your proposal).

How much evaluation or proposal you use also depends on who your primary target audience is. For instance, let’s take the controversy over the NCAA’s classification of college athletes as unpaid amateurs:

Suppose we are writing paper focusing on this topic. Suppose our argument–or at least, the earliest inkling or starting point of our argument–is that, yes, these athletes should be compensated more fairly.

What are some possible target audiences for such a paper? (There’s more than one possibility.)

sports fans: a little evaluation targeted toward them because they affect the bottom line

students athletes themselves: proposal

higher-ups: people who write these rules (ncaa?); administration at the colleges themselves: evaluation; don’t see it as a problem–don’t appreciate the extent to which it is a problem–get that it’s a problem, just not an urgent one

For each of these groups, which stasis feels most appropriate–evaluation or proposal?

How might the other stases (definition, cause-consequence) come into play as we make either of these bigger, broader arguments?

definition ofver the status of these players: what is an “amateur”?

causality: the more it gets publicizied, the worse the effects are for the higher-ups

Group exercise

Get into groups of at least two people.

Groups to which I assign an odd number will brainstorm to come up with an argument that–based on the target audience for the argument–would require prioritizing evaluation over proposal. Remember, the exigence in this case is that not enough people (or not the right people, given the problem you’re trying to solve) get that some important thing is a problem in the first place.

Groups to which I assign an even number, you’ll come up with an argument in which the burden lies on the proposal side of the equation. Remember, the exigence for an issue like this resides in the fact that, while everyone agrees that this important thing is a problem, nobody (or nobody within the “right” target group) can agree on how to solve that problem.

You have 15 minutes. Feel free to use the internet in your search. We’ll discuss the results thoroughly after you’re done.

Now, let’s work from your topics and try to develop them into fuller, more internally structured arguments–exactly the kind you should be shooting for with the Argument Essay.

In particular, we’ll think about any spots or areas in which the definition or causal stases may come into play as we develop the argument.

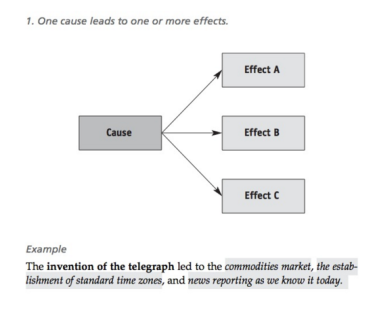

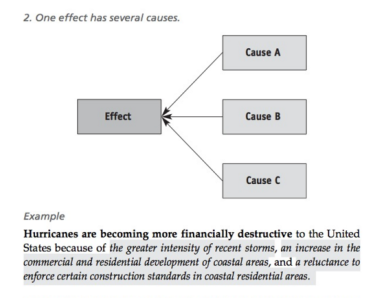

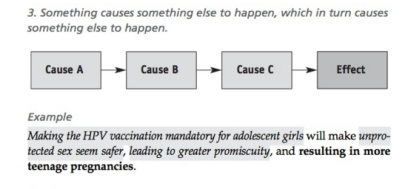

A little on the causal stasis:

Group 1: SAT is not a good measure of intelligence. Target audience=admissions people at universities. These aren’t the students–hence need to prove that it’s a problem

prove that there’s other causes for someone doing poorly besides the “intellect” it’s testing

Group 2: the water is unsafe for consumption and to solve it we should do the following:

p[rimary: govt officials; secondary: MI residents (beyond Flint residents)

cc: if you don’t fix this, these bad things will happen

disagreement over urgency

Group 3: school dress code k-12 is too strict

target audience: superintendents; why the status quo is a problem

define dress code currently; affects student outcomes;

Group 4: gun control; legislation needed–poroposing certain models of legislation; american citizens and legislators

definition: setting targets or benchmarks; cause-consequence: either we don’t do this and it gets worse or we do something

Group 5: SAT is ineffective–college administration

definition: clarify your sense of the way SAT is administered

cause consequence: can cause otherwise qualified students to not get into college on the basis of one test or one day

Group 6: campus needs more parking spaces

eval = administration; proposal side = students;

definition: define poor parking

cause: students give up and go home; lateness affects learning and instruction

Group 7: gun control; evaluation

voters

definition: assault weapon

cause-consequence: restricitng won’t have the intedned effect